Charlotte Betts is another fan of the seventeenth century and writes fantastic award-winning romantic novels set in the Restoration period. She invited me to take part in this writing process blog hop and you can find her blog on her writing process

here:

I have done my best to answer the set questions, though it is very tempting to meander off the point!

What am I working on?

I'm working on two things, one a big thick adult novel, and the other a slimmer title suitable for young adults as well as my adult readers. The big novel is a novel based around Pepys's diary. I have used Pepys's Diary for so many years as reference material for my other books that I just could not resist! It tells the story of Pepys's most famous obsession, his wife's companion Deborah Willett. I have to say, it does feel slightly odd writing about someone with the same first name. Fortunately Pepys himself soon shortens it to Deb, which feels a little more comfortable!

The second smaller novel is part of a series of novellas based around the life of highwaywoman and royalist Lady Katherine Fanshawe -

see my previous post. The first volume was told from the point of view of her deaf maid, and is awaiting editing. I'm on the second volume now which includes the Battle of Worcester in the English Civil War, and is written from the point of view of a ghost. This is a slightly scary thing to do, but very enjoyable. I turn to that when I get stuck with the big book, or at night when it's dark!

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

Rather than writing about Kings or Queens - immensely popular in historical fiction, just look at those shelves groaning with books called 'The Queen's ---' (fill in the blank, but no, The Queen's Doughnut' is not acceptable) - my books are written about ordinary people. I love reading those books about royals though, I recently read 'The Queen's Exiles' by Barbara Kyle and it was a wonderful read.

When I say ordinary, that doesn't mean the characters are dull, in fact the opposite. They are the movers and shakers that shift society into different ways of thinking. I like to have multiple points of view in my novel, so that a broader view of the historical period is painted for the reader. I often write from the male as well as female perspective, so male readers are often pleasantly surprised to find that the book works for them too.

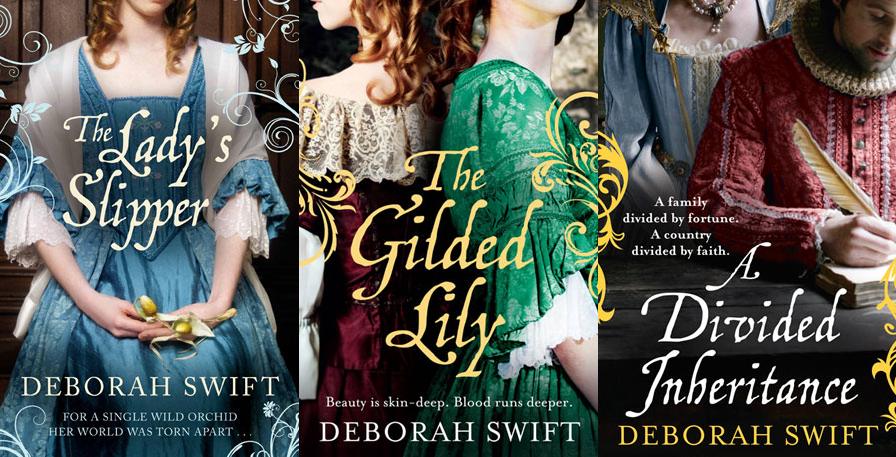

My books embrace themes that matter to me. For example the underlying question in

The Lady's Slipper is: who owns what grows on the land? Is territory something worth fighting for? The setting of the English Civil War, and the battle for the lady's-slipper orchid's survival meshed perfectly together to explore these themes. My other two novels, equally, are underpinned by ideas that I wanted to look into for myself. I enjoy meaty, complex reads with adventure and romance and a strong sense of atmosphere, so I expect that's what I'm trying to produce!

Why do I write what I do?

I fell into writing historical novels by accident, when I was studying for an MA. The first novel started as a writing exercise, but it just kept on growing! By then I'd found that I loved it. Historical fiction uses some of the skills I learned in my previous job as a designer for stage and TV, such as the ability to reearch and plan, and manage my own time, and the ability to think around insurmountable problems (essential when plotting!). I am passionate about the past, and love anything old and interesting. My ideal day out would encompass a visit to a historic house or museum or archives, followed by afternoon tea (with scones and jam, naturally!). When I launched A Divided Inheritance we had exactly that sort of afternoon at Leighton Hall, and I hope my guests enjoyed it as much as I did.

How does your writing process work?

I wish I knew! To be honest I'm a bit chaotic whilst I'm writing. I'm like a magpie, picking up scraps of this and that and scribbling snippets in notebooks. I have a big batch of research books and far too many 'favourites' on my google task bar, of things I am reading as part of the initial 'throw mud at a wall' process. I'm also really motivated by pictures, so I collect a mass of visual information, postcards, and more web favourites. This can take a few months, but happens whilst I am finishing and editing the previous books. Only by doing this can I know if I have enough material and interesting stuff to sustain a long novel and eighteen months worth of research and writing.

After this, some of the mud sticks (I hope!) and I start to draft. At this point I have a solid idea of the story, and the historical basis for it, but no details. On my word doc I lay out arbitrary chapter headings and start to fill in the detail. My first draft is what other people might call an outline, and it follows the chronology of the real history I'm writing about. But - if there are scenes that excite me I can't resist having a go at writing them, so I don't torture myself, I just go ahead and do it. Once I've done that sort of a draft, with some scenes fully written and others just noted as 'Chapter 5 - Mother dies', I'm ready for a second go at it. In this draft I try to fathom out how to make the scenes I haven't written yet more interesting or gripping until I have to write them. This involves more research and book gathering and tinkering with the plot. And so it goes on, draft after draft. The actual writing is like re-living the scene as I put it onto the screen. Eventually I end up with a full novel, all of which I enjoyed writing. At this point I'll put it away and work on something else for a bit to get distance.

When I pick it up again I start editing, and this sometimes involves re-structuring and sometimes only nit-picking. Mostly it is about re-ordering the story into a logical flow. This is the point where I realise what the novel is really about, so I go back through it again and re-write with that in mind.

So you can see, it is not exactly a quick, streamlined process, but it's more of an organic building-up over time, where the plot events accrue significance as I'm working.

I wish I could be the sort of person who sits down with a perfect plan and writes to it, but I'm just not. Initial ideas are always the most obvious ones - I need the juxtaposition of a lot of different stimuli to delve deep enough and make the right sort of connections to get a juicy story.This is why I think I'd be hopeless at writing crime - where I expect you have to know exactly who has done it from the outset, and why, and everyone's alibis! My method gives me a lot of 'wiggle-room' if I find a better or more interesting idea. I do love books on the craft of writing though, and fantasising that I'll be that super-efficient writing machine next time. . .

Eliza Graham writes historical fiction under the pen name Anna Lisle. She also writes fiction set in contemporary times but with a historical twist. Her most recent book is The One I Was.

The One I Was

1939. Youngster Benny Gault, a Kindertransport refugee from Nazi Germany’s anti-semiticism, arrives at Harwich docks, label flapping round his neck, football under his arm, and a guilty secret in his heart. More than half a century later, Benny lies on his deathbed in his beautiful country house, Fairfleet, his secret still unconfessed. Rosamond, his nurse, has a guilty secret of her own concerning her mother’s death in a fire at Fairfleet, years earlier. As Benny and Rosamond unwind the threads binding them together, Rosamond must fight the unfinished violence of the past, now menacing both Fairfleet's serenity and Benny's last days.

The One I Was is a novel about shifting identities and whether we can truly reinvent ourselves.